The Breakdown

WELCOME. Now, before we fasten your belts – they’ll keep you safe against the enormous Gs as we break the atmosphere, gain the vast promised land of outer space – it’s as well as we run through a final checklist to ensure a safe and enjoyable journey.

So. Question. When names like Broadcast, Stereolab, Vanishing Twin and Add N To (X) are dropped into conversation, do your eyes take on a glimmer, a grin form on your lips? Good (*Ticks box on clipboard). Furthermore: when more abstruse names such as Morton Subotnick, Jacques Loussier, Pierre Henry crop up, are you all ears, enthusiastic, ready to propound the relative merits of Silver Apples Of The Moon against Les Jerks Électroniques De La Messe Pour Le Temps Présent Et Musiques Concrètes Pour Maurice Béjart? Excellent. You have exceeding cool friends, may I say.

Do you dream of lab coats, clipboards, and a hall of abstruse circuitry, tape spools, wiring and valves, all at your disposal? This is wonderful news. You’ve booked aboard the correct flight. We have ignition.

For this Friday the folks behind excellent Canadian imprint We Are Busy Bodies, responsible this year alone for a clutch of rare African jazz reissues and an excellent, melodic, free-jazz debut from Peace Flag Ensemble, have been digging in the crates off-world to bring back not one, but two, of the rarer early electronics records of the pioneer era: Tom Dissevelt and Kid Baltan’s 1959 set The Fascinating World of Electronic Music, and Tom Dissevelt’s 1963 LP Fantasy In Orbit, the record which we will be primarily concerned with journeying into here.

It may be as well to contextualise the state of electronic music in the 1950s to see where Tom Dissevelt was working: the past is indeed another country.

Although electronic instruments of sorts had been around for a decade or two: the ondes Martenot had been invented in 1928 by the French radio operator whose name it takes, the same year Leon Theremin patented his eerie magnetic-field generative, eerie creation, neither had made too much of an impact; the former, built to order, was being used by French classical composer Olivier Messiaen but few others; it’s arguable that the theremin was a way away from finding its niche, a curio inveigled into albums such as Les Baxter and Harry Revel’s sentimental and treacly 1947 set, Music Out Of The Moon.

Elsewhere a magnetic-tape underground was flourishing in France: the group centred around Pierre Schaeffer had established the principles of musique concrète, concerts in Paris were well-received; the highbrow and the cognoscenti flocked around the delicious possibilities and the first purpose-built electro-acoustic studio was built by the French national broadcaster, RTF.

By 1956, Hollywood was in on the action with Louis and Bebe Barron’s groundbreaking, entirely electronic soundtrack to the off-word sci-fi Forbidden Planet, Shakespeare’s The Tempest recast on an arid planet. Electronica as a musical form really entered the public consciousness for the first time. It could, companies and broadcasters worldwide thought, be the future … .

In the Netherlands the electronics and media giant Phillips was watching with a keen eye. It had an in-house research and development laboratory, the Natlab, founded in 1914, which operated on Einstein’s maxim “Everything that is really great and inspiring is created by the individual who can labour in freedom” – tldr, carte blanche to experiment. It recruited Tom Dissevelt, who had carved out a name for himself as a jazz bassist, alongside renaissance man Dick Raaijmakers – an engineer, cultural theorist, and artist. Could there be such a thing as an electronic pop? was the question Phillips posed.

(Oh: here’s a short, contemporary clip of Tom and Dick explaining how electronic tape music is made – there’s a translation in the sub-scripted comments).

By the mid-1950s, both were fully installed in investigating such a proposition. At the Natlab, ongoing research was looking at electronic drums, resonators, synthesizers, mixers, oscillators and tape recorders, among a host of other nascent developments. Philips really wanted a piece of popularising electronic music.

Indeed, Raaijmakers would perform an electronic music concert at the 1958 Brussels World Fair – the setting of the famous Atomium sculpture, heralding a bright scientific future in a purpose-built pavilion. It’s said it had an enrapturing effect on those who visited – not least among whom was a then 12-year-old Ralf Hütter… .

The first fruit of the Raaijmakers-Dissevelt navigations (for which Raaijmakers assumed the oddly hiphop name, Kid Baltan) was a single , “Song of the Second Moon” in 1957. Click through, have a listen; and here’s the neat thing. Because rather than being a filmic atmosphere or a far-reaching symphonic essay, “Song Of The Second Moon” is electronic pop, with a shuffling rhythm, cosmic melodic fancy, but y’know, a beat, a break even; an asthmatic rhythmic quality which would resurface on The Human League’s “Being Boiled” two decades on; and direct antecedents ranging up through Hot Butter’s “Popcorn” and into Kraftwerk and beyond. It features on The Fascinating World of Electronic Music , also this week, remember.

This long-playing electronic dish was still too rich for general consumption, however, and proved disappointing sales-wise. In 1960, Philips decided it was no longer viable to host the NatLab, which upped sticks and rebranded as STEM, the Studio for Electronic Music, at the university in Utrecht.

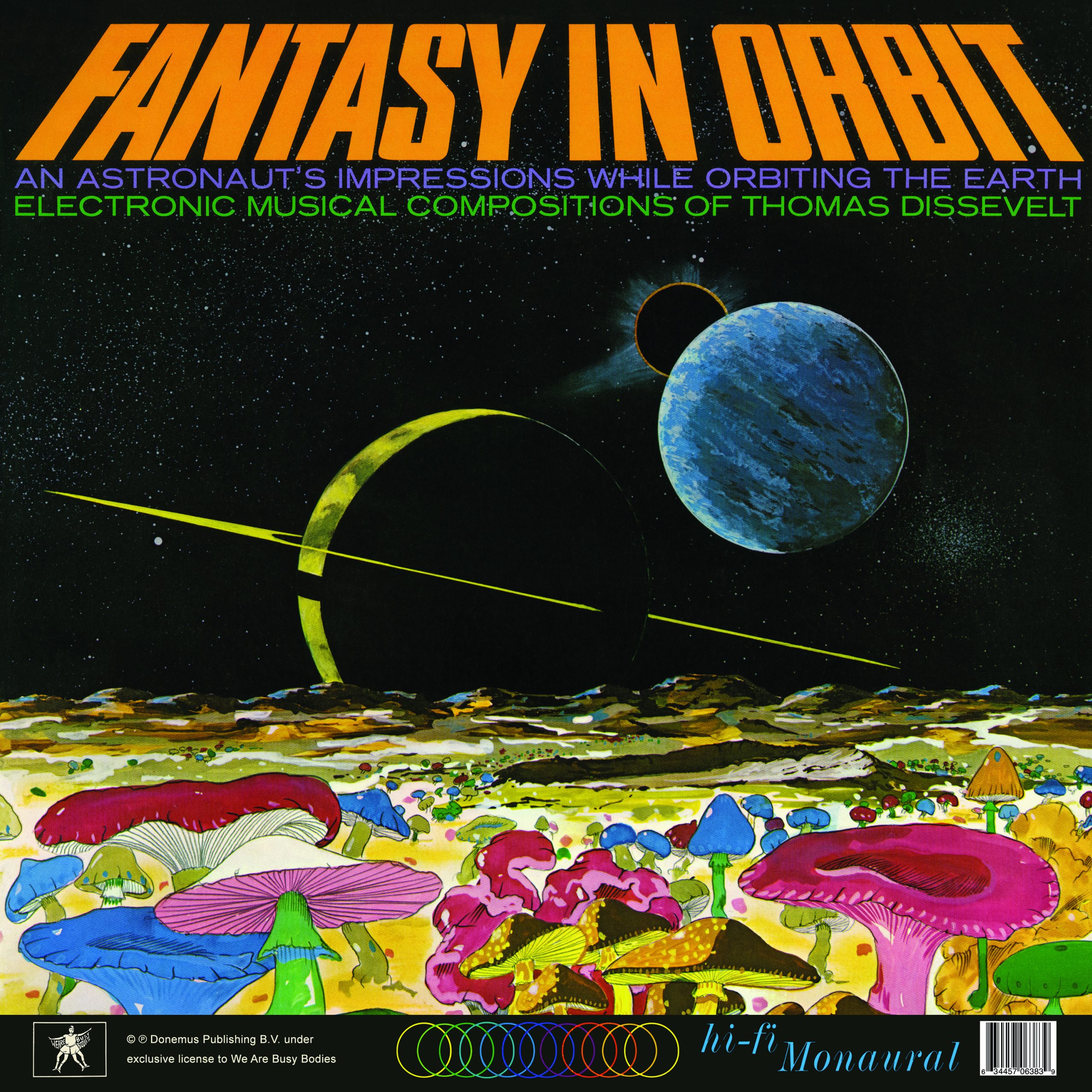

It’s in that post-Phillips era then that Tom ventured this next album, the one we’re gathered here in appreciation and expectancy of: a space oddity a half-decade years ahead of Bowie, and capitalising on the new astral future we were poised to embrace. Fantasy In Orbit would receive a staggered release, coming out in the Netherlands in 1963, with British and North American pressings following in ’65. It’s the American full-dayglo cover artwork that’s favoured by the We Are Busy Bodies reissue; I have to declare a preference here for the more austere, three-colour original and British issue, which speaks more of a world with an eye on the stars, but subfusc and shaking the shackles of rationing and national service. Still, such are minor quibbles.

The album was birthed into a world of the Dr Who theme and The Tornadoes’ “Telstar”; a world in which Gagarin and Project Mercury had captured imaginations. It was intended to appeal to this global curiosity, natch; and sought to do so by chronicling in sound an entire mission, which it does from the pulsing and echoing “Ignition”, thrust and flame and pounds per square inch rendered as futuristic chatter; to the sparse, haunting lament of “Re-Entry”, roughly 32 minutes later.

In between times Tom journeys you over the “Atlantic” with an ominous, tonally decaying reading of “Waltzing Matilda” interjecting – yep, you can see Australia from up here; an Antipodean classic reprised later as alien cross-chatter and thrumming thrust.

“Spearhead” whistles and oscillates like a stun gun, allows for the cavernous glimmer of space to twinkle and hum – introduces you to the vastness and beauty of it all; “Zanzi”, a darker correspondent, all icy solar winds and drone, laying out territory for vast monotones such as Kevin Richard Martin explored earlier this year on his Return To Solaris album. You’re so …. far. From anything. “Anchor Chains” – for how else would one moor a space-ship? – is all popping chatter, spectral organ-like tones, free note flurries and high cicadas which have you looking around the ceiling for the insectoid source.

“Tropicolours” continues in a similar pan-dimensional, busy and curious valve conversation, layers dropping out and resolving once more with insistence, broken beat decades before its conception; “Gamelan” fair rolls with the creaking of joists and comets of sound; this is how the music of the world looks, Tom seems to suggest, from out around the exosphere. Onboard computers sing their lonely circuit song.

“Woomerangs” – a punning conflation of the Australian satellite station, an essential link in the Western space programme chain of command, listens in at the big dishes to the breathy cacophony of radio waves – the bare essence of the human just audible in all that advanced technology; whereas “Pacific Dawn” presents as the bubbling joy of oscillators masking some entirely distant psychedelic jazz vamp.

Both “Gold And Lead” and “Mexican Mirror” play out in the higher registers, oscillating fantabulously with the eerie distant tones of pulsar emissions and circuitry; chittering with a tribble-like cuteness.

Bleeps, drones, tone sweeps echoes, the sound of a galaxy we were on the verge of inhabiting; it’s a record at once wholly of its time and on two layers, wholly of ours – since we live in that distant 21st century of the forecast offworld colonies, floating, cuboid bachelor pads and, more accurately, weird electronic music.

And you know that thing whereby Morricone has somehow convinced us, become synonymous in our minds with the true sound of late 19th-century and early 20th American west being a lone whistler, some tubular bells and the scorched twang of the Fender Telecaster, first on the market in 1950? An incredible performed illusion?

Well, by the same token, do we not look to the sounds of Fantasy In Orbit and other such astral touchstones of the era – the Meeks and Derbyshires and Gil Melles – as the true sound of space? The oscillating telemetry, the eerie tonal swoops, the sounds of machines created by us going about their essential business in deep space among the flares and asteroids and unimaginable distance and chill.

That’s why this album is such an intuitive, race-memory trip and essential for any retro-electronicist in your life. Hurry now, should you wish a seat beside the portholes and away from the fins; space is limited. You won’t believe what you see and hear out there.

The album comes reissued with both mono and stereo versions in a 2xLP pack.

Tom Dissevelt’s Fantasy In Orbit: Round The World With Electronic Music / An Astronaut’s Impressions While Orbiting The Earth and his collaboration with Kid Baltan, The Fascinating World of Electronic Music, will both be reissued by We Are Busy Bodies this Friday, November 12th, digitally and on limited vinyl; the former is limited to 500 only and the latter to 1,000, so get your skates with the pre-order – they’re going pretty damn quickly. You can order the first title here and the second, here.

No Comment