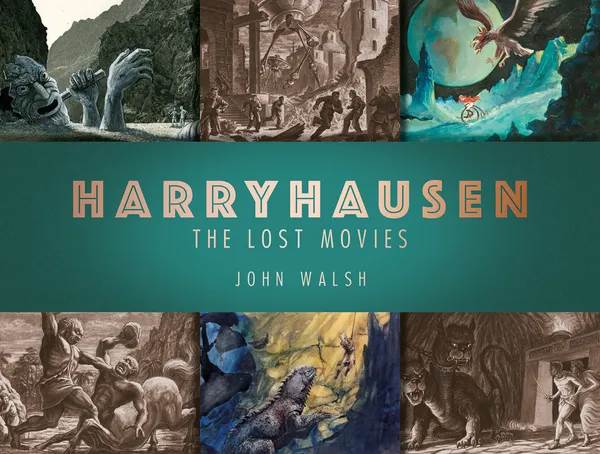

The late Ray Harryhausen (1920-2013) is widely regarded as the person who pioneered visual effects for motion pictures as a craft. The stop-motion animations he provided for films like Jason and the Argonauts (Don Chaffey, 1963) and Clash of the Titans (Desmond Davis, 1981) broke new ground in their respective eras. Author and filmmaker John Walsh, a friend of his and trustee of the Ray Harryhausen Foundation, has published a book called Harryhausen: The Lost Movies, which documents the projects on which he worked which never came to fruition. I talked to Walsh about these lost films.

He explains that one of the earliest films he discusses in his book was an early version of The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, of which Terry Gilliam eventually made an expensive flop in 1988, as well as an adaptation of HG Wells’ The War of the Worlds. ‘‘Terry’s film was quite controversial because it was expensive and it wasn’t particularly successful at the time, although it’s highly regarded now. Ray wanted to do it in the 1950s and he had test footage of that and lovely artwork, oil paintings, and so on. Also around that time in the late 1940s, Ray wanted to make The War of the Worlds. This would have been the first cinema outing for HG Wells’ original. Ray would have done it in the original style and the Martians would have been on tripods. These metal dishes with tripod legs would have bestrode the landscape. When George Powell made his version in the 1960s, he went down the more Thunderbirds route and just put saucers on strings.’’

Another unfinished project Harryhausen attempted to develop a few years later was an adaptation of Robert E Howard’s Conan the Barbarian stories, Walsh explains. ‘‘Ray tried to get Conan going in the late 1960s and contacted the publishers to basically get the options for it and experienced difficulties because the Robert E Howard books are very explicitly violent. So much so that when they went to the studio, the studio was like ‘yes, this is good because it’s a novel that’s popular but there’s no way we’re gonna give you the money to do something that is ultra-violent on one hand and sword-and-sandals on the other’. They felt those two genres wouldn’t mix and the main audience would have been quite a male, juvenile audience and they’d have been prohibited from entering because of the violence and actually there’s quite a lot of sexual content as well in some of the books. So they were in a position of ‘we could commission it, we could option the novel, we couldn’t get a studio to back us, therefore we’d have to water down the content, therefore we’d lose under the option the rights to what we’ve bought and probably the representation’. Robert E Howard wouldn’t have allowed that anyway.’’

Walsh goes on to explain that Harryhausen’s experience on this project demonstrates his aptitude for getting ahead of industry curves. ‘‘On the option, they get a sign-off on the screenplay. So that was frustrating because Ray had effectively predicted – you see this throughout the book – different trends. The studio was wrong to say sword-and-sandals and ultra-violence don’t work because when John Milius’ film Conan the Barbarian with Arnold Schwarzenegger came out in 1982, it was a big success. It was an R-rated film in the States and similarly rated here, yet that set the footprints which you can follow all the way up to Game of Thrones. Ultra-violence in fantasy film and television started with Conan and continues right up to the present day.’’

Around the same time, Harryhausen’s forward thinking came up against studio executives’ conservatism and risk aversion on another project. ‘‘In the late 1960s, Ray went to the head of Hammer Films, who was looking for something else to do after 1 Billion Years BC, which was their most financially successful film. It wasn’t a Dracula or a Frankenstein, it was the dinosaur film Ray had made with Raquel Welch. They said ‘Ray, let’s go again, let’s do more dinosaurs’. Ray was like ‘well, we’ve done that’ and they said ‘let’s do it again’. He wasn’t interested in the sequel with which they went ahead anyway. He said to them ‘I think there’s another genre that’s due for a revival’. They said ‘what’s that?’ and he said ‘well, do you know this film from the 1930s called The Deluge? It’s basically about San Francisco being taken over by a tsunami’. He said ‘I think we can redo it and set it in London’. Ray did some beautiful artwork for it, which is in the book, and they said ‘no, this is 1967, I don’t think the disaster genre’s due for a re-emergence’. Of course, the 70s happened and it was nothing but disaster films. The Towering Inferno, The Poseidon Adventure, Airport.’’

Harryhausen: The Lost Movies also features concept art for an unmade film on which Harryhausen was working just before Clash of the Titans that would have blended science fiction with historical epic storytelling. Walsh explains: ‘‘Just before Clash of the Titans, he was developing Sinbad Goes to Mars, which sounds like a fantastical, comical idea, but the artwork in the book is by a famous illustrator called Chris Foss and he was simultaneously doing concept art for Ridley Scott’s Alien, Stanley Kubrick’s abortive attempt at AI in 1981, and Alejandro Jodorowsky’s unmade version of Dune. So the artwork we have for Sinbad Goes to Mars has that real sort of industrial, brutalist look and feel about it, and Chris never kept copies of the artwork. The originals are in the Ray Harryhausen Foundation, he created four paintings, one of which wasn’t finished. We contacted him and he finished it for our book. So there are little exclusive bits of art in the book.’’

Walsh adds that Harryhausen’s retirement from the film industry after Clash of the Titans at the relatively young age of 61 was borne of necessity rather than choice. ‘‘In 1981, Clash of the Titans was more successful than any of his other films. It had a budget 17 times larger than The Golden Voyage of Sinbad’s, it made more money than any of their films, it’s the most watched of their films, and in Europe it was more successful than Raiders of the Lost Ark. So by every measure, they were waiting to do the next film, and the next film was Force of the Trojans. That should have hit theatres in 1984 and it didn’t. The story of that is quite interesting and complex but MGM was going down at the time financially, despite having successes like Clash of the Titans, and the rights then were with MGM for quite some time. The landscape in Hollywood was changing.’’

‘‘By the early 80s, people were less interested in fantasies set in the olden days, if you will, whether it was Greek mythology or Arabian adventure. The new kids down at Industrial Light and Magic with their different animation techniques called ‘go-motion’ and early uses of computers with cameras were making Ray’s form of animation seem slightly old-fashioned but Ray had every intention through the 80s of making Force of the Trojans. He developed a film with Michael Winner called People of the Mists. There were lots of other projects he was involved with, they’re all in the book, and Ray was still seen as relevant. So when we look back from this perspective, it was his last film. The industry retired from Ray, not the other way around. Ray was quite sorry about some of those unmade films and we at the Ray Harryhausen Foundation now are officially developing Force of the Trojans as a new movie.’’

Slightly surprisingly, Harryhausen apparently had an abortive post-retirement opportunity to work on a now hugely successful franchise. ‘‘If you’re a Marvel fan, you might be interested to know that Ray turned down (and it’s in the book) the very first Marvel movie. He was approached by Stan Lee in 1984 with a full screenplay for the first X-Men movie. That’s quite a long time ago and it never saw the light of day. Not because Ray wasn’t involved but certainly because lots of films didn’t see the light of day. Nevertheless, we have all the materials. It’s just the script, anyway, from Stan Lee and the handwritten Stan Lee notes. So Ray often would turn things down, either because there wasn’t the time or because he was working on something else. He also turned down the chance to work on David Lynch’s Dune in that same year, 1984. He would have worked on the sandworms and the third-stage guild navigator that you see at different points in the film, so it is fascinating that the outside world saw Ray not as a safe pair of hands but as the go-to person for visual effects on a big-budget film.’’

I conclude by asking Walsh how he feels about his new book and the opportunity it has afforded him to raise public awareness about some of his late friend’s lost films. He takes no time to consider his response. ‘‘For me it’s been a book that’s been 100 years in the making because Ray would be 100 next year. I’ve spent two years on it but for all of the time that I knew Ray, going back to when I was an 18-year-old film student 30 years ago, he was always cagey about the unmade films. I’m pleased that finally his artwork and his great work will no longer be lost in the shadows. It’s now out there.’’

Harryhausen: The Lost Movies is available to buy now from Titan Books.

No Comment