The Breakdown

OVER two phases of potent reports from the real England, with an interregnum of two decades between, David Lance Callahan and The Wolfhounds have consistently filed detailed documentation from the real England – not the England of climbing roses and parental-secured internships and unearned increments, but the England I knew and grew up with: the shonky “Ropeswing” out past the reservoirs, where the fly-tipping eases; the spirit-crushing search for accommodation, “Rent Act” (and how relevant that tune is now); the hopes and yearnings of the migrant shop keeper, from last year’s arcing Electric Music. Real lives, lived, unembroidered by ISAs and gilts and a second Range Rover, closer to the floor and the stars and the raw reality of it all.

And it’s that latter tune, “Song Of The Afghan Shopkeeper (After Ben Judah)” which is the best pointer forward to this debut solo album from The Wolfhounds declamatory lyricist David Callahan, who’s followed his longtime creative partner guitarist Andrew Golding in stepping outside The Wolfhounds on a foray in a different musical direction.

Andrew released his second solo set as the anagrammatic Dragon Welding, The Lights Behind The Eyes, back in late spring; and a fine album of six-string instrumentals it was too, encompassing everything from the glorious, whammy-bar noise chaos of his parent band to glass-brittle, Vini Reilly-like essays; “a new ambient folk for a beleaguered island”, we summated it. Andy’s got form, having released one previous, self-titled foray two years back; David has also, in the form of relatively low-key single for Slumberland’s singles club, “Strange Lovers” – an echoing, acoustic guitar and bells lament, but chill and bleak.

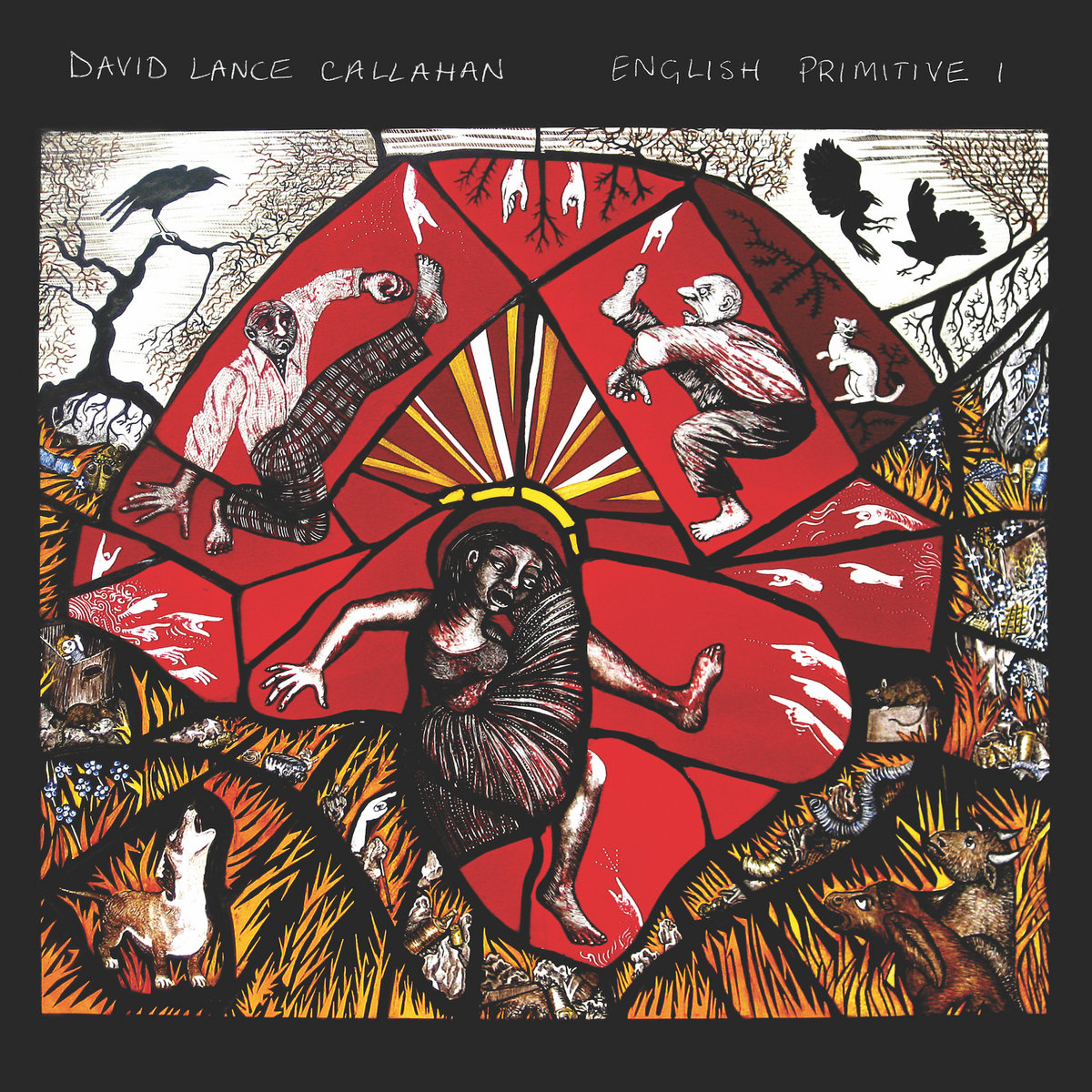

On that form then, it’s really very intriguing indeed that English Primitive I present as a deep, complex excursion into the raga-folk form – taking as a sonic touchstone a certain brand of exploratory British psychedelic folk at its height from ’68 to ’72, and bending it to a new and more earthbound, socially documentarian thrust than maybe artists such as The Incredible String Band and the long-lost Spriguns of Tolgus had in mind, when they were exploring their fusion of cult religion, communal living, LSD and the folk music archive.

From a standpoint roundabout here in time, that sort of wyrd-folk looks to be a regretful casualty of the punk wars, whose main aim was at the jesus-christ-must-you virtuoso flab of Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Yes, et al who, like the modern-day Tory party, seem to have lost any kind of relationship with the common man they claim to fanfare, a breed apart by absolutely any and every criteria, the Eloi whooping it up in desuetude with no idea how they look and sound out beyond the confines.

That flaming two- and three- chord arrow took down the prog, with relief; the hippy associations of acid folk saw it burn to the ground too, and it’s a good thing that reappraisal over the past decade or more has seen a real renaissance for artists from the Sixties’ UK folk scene. There was, and is, real power in much of that era – go listen to Dolly and Shirley Collins’ Anthems In Eden for instance, or Comus’ First Utterance, as a more demented flip.

Apart from, then, a first precursor within The Wolfhounds’ songbook of that song of the Afghan shopkeeper, we have no pointers as to why Callahan has emerged now with such a forceful, at times luxuriant, raga-folk record – whether it’s the deep self-immersion of the lockdowns or what, we’re not told; what is certain is that it absolutely defies any prejudice you may entertain about him heading into folk.

After all, The Wolfhounds have always been concerned with us, the folk, and our tales. We’re the English primitives whose lives he seeks to recount, bringing us seven tales of the less cushy life couched in a mutant Eastern scales-meets-post-punk fire.

The tone of the record, both small- and big-P political (and if you follow Callahan anywhere on socials, you’ll know the postwar settlement espoused in this song is absolutely a hill he would die on – and rightly so) is set in the raw, male-female close harmony of “Born Of The Welfare State Was I” – the state as force for good, cradle to grave, a “safety net to catch us all / Is now sagging, with even bigger holes”, as the rents and tears widen and more fall further and further through. That such sad, clear commentary on where we’re at manages to also be spirited and proud, open chords and drone strings allowing for a flute to even venture a merriness, is quite the thing; allowing for a hope among the managed decay of civilised national care. (That female voice? It’s Katherine Mountain Whitaker, collaborator across recent Wolfhounds albums and former singer with Welsh indie-punksters Evans the Death).

“Goatman” ventures back to the world of the rope swing, the odder, scarier world of early adolescence when marginal figures such as this impinged as you explored the edgelands, the scrapyards, the quarries and parched paddocks – coming roaring at you if you climb the fence into his territory. Go too far, “and you’ll be lost forever”. The Goatman, the modern folk devil; we had one around us, lived in a caravan, albino-white hair, malicious stare. There’s a metaphorical layer at work here, too: he shares all his possessions to a communal end; if he gets you, you might as well be dead – the demonisation of common purpose in an age of turbocapitalism. Callahan’s raga guitar is muscular, ringing, has a nicely punk edge.

And on the seemingly twinned “Foxboy” – another, singular creature of modern suburban myth, that raga grows fiery as a Spacemen 3 live bootleg, blues-fuzz-droning, biting with acid flourishes, tabla in pulsing support. Callahan’s voice is resonant and instrument-like, part submerged in the curls of strings and guitar roar. The strings take on a siren stridency, come back for one skin-prickling flourish after the song seemingly ends. It’s absolutely cracking. Here, listen for yourself.

With the goatman and the foxboy passing back into their twilit thickets, another pair of seemingly conceptually twinned tracks follow: beginning with the skeletal and personal-political “She’s The King Of My Life”, gazing out to Canvey Island and the raw glory of Wilko Johnson; Callahan here vocally more laidback in recounting a tale of a romance or an addiction, the distinction deliberately indistinct – “I know my weakness … but I’m making progress,” he sings. Notes bend and twang with an early blues sides raggedness, passion and amplification bringing the seethe. And does hookline, “She’s the king of my life” resolve as “She’s the king of my lies” right at the end there? It has an addled folkdance swing; recalls as well Bright & Guilty era ‘Hounds in its grey-skied, bleakly cheery resignation to the hamstringing of circumstance.

The coupled “She Passes Through The Night” rings drone clear and strong, is the most lush track on the album; grand as if Robert Kirby, the man behind Nick Drake’s string arrangements, had spent a year contemplating pastoralism through the prism of the hellish, modernist grandeur of South London’s Heygate Estate. There’s much beauty, but the beauty of a river in spate. You might take care not to be swept in. You may not have that choice. Katherine’s echoing, eerie counterpoint brings a real spectre-folk depth. Album highlight.

And that string-sorrow remains in play for “One Rainy September”: a sparser, more naked tale of a return to Civvy Street from the companionship of the Army to a wife and a child who barely recognise the man who pitches up; and by extension, a man spat back out into a world he no longer recognises, the tune proceeding over an organ drone, the guitar initially shorn away. As with other tracks here, the pun-refracted folk has a slow-burn, contemporary bone-chill and quiet desperation last seen over in Manchester at former labelmates King of the Slums: “A lack of life skills and a woman’s cold shoulder” is the fate crashing down on the nameless protagonist. “You don’t understand!” is the retort: “I needed you / Almost all of the time.” The strings build and wail, cry for the small life broken.

After that eight-minute, widescreen odyssey, the small writ large, it’s a reverse treatment for the closer, “Always”, in which the sharp-suited and perfect teethed of the laissez-faire centre and their faux-benevolence are presented in a simple fireside arpeggio, almost a cheery, beery lullaby – that flagon soured with their stifling discourse: “We’re always right / always …. we’ve done very well … we won, we always win / always.”

Seven tracks might on the face of it seem brief, but as an experience this album is anything but. As with the aforementioned Bright & Guilty, Blown Away, Electric Music, all the parent band’s catalogue, this album will open before you gradually. You’re gonna have to work at it a little; no puppy of a record, eager to please, this. You can sense immediately how much more there is to be gained from repeat listening and how much yet to unfold. Other killer lines reaching out; other crescendos catching you with their amassed energy. It’s the sort of record that one day ought to pitch up on social history syllabuses as a true reflection of a broiling, fracturing period in which it looks likely the humble populous may come off worst. And yes, there is a I in the title; which, as implicated, means a second, mirroring instalment is on the way, culled from these same sessions.

What a time to be alive. Be glad that David can see clearly and crystallise it for us.

David Lance Callahan’s English Primitive I is out now via Tiny Global Productions digitally, on CD and on vinyl; pick up your copy over at Bandcamp now, or from any good record store.

No Comment